Make the Ordinary Sacred

The past two years have been interesting, as we have entered into and through a pandemic, learned new skills, and discovered things about ourselves we may not have known were there. In the midst of that time, I have found myself reading poems, articles, and stories that speak to real life and emotions. The overwhelming number of things I’ve read that spoke to me were the courageous things. The poems about picking yourself out of bed when depression told you not to, reminiscing about eating a meal with your grandmother before she passed, and harnessing the joy of a child’s laugh to name a few. The elements that all these stories had in common was an elevation of the ordinary. They celebrated regular people cherishing the seemingly mundane but also recognizing the effort it takes to do so.

The past two years have been interesting, as we have entered into and through a pandemic, learned new skills, and discovered things about ourselves we may not have known were there. In the midst of that time, I have found myself reading poems, articles, and stories that speak to real life and emotions. The overwhelming number of things I’ve read that spoke to me were the courageous things. The poems about picking yourself out of bed when depression told you not to, reminiscing about eating a meal with your grandmother before she passed, and harnessing the joy of a child’s laugh to name a few. The elements that all these stories had in common was an elevation of the ordinary. They celebrated regular people cherishing the seemingly mundane but also recognizing the effort it takes to do so.

The poems that relish and elevate the small things are the ones that have the most impact. For example, Patricia Smith has a poem entitled “When the Burning Begins” where she details making cornbread with her father before he passed. While the act of making cornbread isn’t particularly exciting, the vibrant language, colorful storytelling, and active wordplay allows us to exist in the moment and have a greater appreciation for what that act represents.

When you are crafting your own work, take a look at the things around you. What is something that you do every day as a ritual? What does that look and feel like? What makes it something special to you? Asking yourself those questions can help you find and define a purpose in that routine. Perhaps you brush your teeth a certain way because your mother told you that when you were younger and now it’s also a way to honor her. Perhaps you eat a certain meal on a particular day because it reminds you of something. Take those ordinary occurrences and detail the process of what it takes to create it. There is always some beauty in the seemingly ordinary.

ABOUT ANGELO: Angelo ‘Eyeambic’ Geter is a dynamic poet, spoken word artist and motivational speaker who merges his passions for poetry and speaking into a unique performance that educates, entertains, and inspires. Over the course of his career, Angelo has amassed several accolades. He currently serves as the Poet Laureate of Rock Hill, SC, and a 2020 Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellow. Geter is also a 2019 All-America city winner, 2018 National Poetry Slam champion, Rustbelt Regional Poetry Slam finalist, Southern Fried Regional Poetry Slam finalist and has performed and competed in several venues across the country. His work has appeared on All Def Poetry, Charleston Currents, and the Academy of American Poets “Poem a Day” series.

BRING YOUR WORDS TO LIFE WITH ANGELO: Join Angelo for Spoken Word: Poetry and Performance, a three-part class dedicated to the art of spoken word and poetry slam. Examine spoken word work to demonstrate how literary devices employed in traditional poetry are expanded in this genre. Participants will be guided through several prompts and exercises to help them craft their own original work. Participants will have the opportunity to read their spoken word pieces and receive feedback. This class will show you how to literally bring your words to life from the page to the stage. More information here.

Note: This class meets on three Tuesdays, May 10, 17 and 24, 6:00-8:00 pm.

Proof of full Covid vaccination is required to attend in-person Charlotte Lit events. Send a picture of your vaccination card to staff@charlottelit.org

“I’ve Always Wanted to Write a Book”

When I meet someone new, within the first few minutes, they inevitably ask, “So what do you do?” It’s an innocent question, but one that often leads to an interesting end: “I’m a writer,” I say, and many look wistfully into the distance and reply, “I’ve always wanted to write a book.”

A natural encourager, I invite them to share their ideas. I listen attentively, knowing that the first crucial step to writing a book is often a conversation like this. They try their best to sum up what’s been beating around their heads — sometimes for decades — and in so doing, realize they’ve never tried once to say it aloud. Then they give me the kind of smile reserved for fast friends — for the unexpected society found in the quiet corners of summer barbecues, football games and their tipsy on-lookers shouting in the background.

More than a decade into such conversations, more people than ever are lighting up as they tell me about their book ideas. Maybe it’s just that my friends and I are getting older, and questions of legacy and bucket lists and everything we’ve always wanted to do has become more urgent. Or maybe it’s the time we’ve all had in the last, languid years to dream up new worlds and characters and hobbies. Whatever it is, almost everyone has an idea now. Is it just a passing fad or something more profound: a recognition that the world needs longer, richer stories into which we can sink our teeth?

Sometimes these conversations lead to a practical question: How does one actually write a book? Nearly every time, the light that was so bright in their eyes begins to fade. I have to get up early? I won’t get paid for several years or maybe not at all? I have to convince a string of people, precipitously inaccessible, that my story matters? That sounds too much like work! We laugh and then transition to the next-best thing — a new Netflix series, the strange weather of late, the delicious dip Kelly brought — anything but the dream crashing down around us. We part ways with a tinge of regret.

But other times — and these are the ones I live for — the light of an idea grows brighter. As they ask about my discipline and practice, they begin to think they might want to do it, too. Faced with the long odds of publication and the cascades of rejection, there is a gauntlet thrown down at their feet. In that conversation, in that desire to make their ideas known to a wider world, they take the first, crucial step toward a goal they’ve had forever.

And it happens: they begin to write their book.

ABOUT MEG: Megan Rich has written two books, a YA novel and a travel memoir, and is seeking representation for her third, a literary thriller inspired by The Great Gatsby. She took part in the highly-selective sub-concentration in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan, for which she completed a thesis of original poetry. In addition, she’s a graduate of the Lighthouse Writers Workshop Book Project program. With fourteen years experience as a creative writing teacher and mentor of students from ages twelve to eighty-five, she is passionate about helping others find and refine their voices on the page.

JUMP START YOUR BOOK WITH MEG: Learn to create a lasting connection with your readers, by developing your voice in Meg’s upcoming class Novel Jumpstart, beginning Sunday April 3. In this four-week mostly-asynchronous studio we will help you decide if you want to write a novel, and if so, will help make the journey must less fraught. Through recorded lectures, readings, online discussions, and short assignments, we will examine the structures of stories, protagonists and their journeys, story worlds, story time, genre, point of view — and the habit, discipline, and support needed to get it done. More information here.

Note: Novel Jumpstart a great choice if you’re considering applying for Authors Lab, which begins in the fall.

Disrupting Process

Process, the stages of creating—this is where a writer’s real power is. By being mindful of process and concentrating on the series of steps involved, rather than the final product itself, we end up where we want to be.

Process, the stages of creating—this is where a writer’s real power is. By being mindful of process and concentrating on the series of steps involved, rather than the final product itself, we end up where we want to be.

Process means giving yourself the chance to begin. It’s the best cure if you haven’t written in a while—to allow the half-formed, imperfect words to appear on the page. You don’t need the whole poem or chapter yet. You just need a snippet.

You have likely reflected on your own process. There’s not just one way. We writers love to ask each other such questions. It can become part of our identity: Are you a messy, illegible sticky-note writer? Or a loopy longhand on yellow legal pad writer? Whatever process you’ve developed, I am here to advocate the idea of disrupting it! Invite change. Make experimentation part of your process and see what happens.

Not long ago I started playing around with how I court new work by writing every day and by writing through prompts—strategies plenty of other writers do all the time. But not me, I never had. And I’d perhaps grown too accustomed to my process.

So instead of focusing so much on revision, which I dearly love, I started to focus intentionally on inception. I even started incorporating another form of artistic expression into my process—something I’m not good at, painting with watercolor. This was inspired directly by poet Gabrielle Calvocoressi. I also once heard fiction writer Barry Hannah give a talk along these lines—the value of letting yourself create in another form without trying to become good at it. Creating without a focus on mastery brought play and dreaming back to the forefront.

ABOUT JULIE: Julie Funderburk is author of the poetry collection The Door That Always Opensfrom LSU Press and a limited-edition chapbook from Unicorn Press. She is the recipient of fellowships from the North Carolina Arts Council and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Her work appears in 32 Poems, Cave Wall, The Cincinnati Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and Ploughshares. She is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Queens University of Charlotte.

POETRY 101 WITH JULIE: Explore the world of verse by learning to read poems with the senses of a poet, and come away understanding what you missed in high school and college lit classes. Prose writers will gain a deeper appreciation of poetry and some inspiration—for ways to integrate poetic devices into their prose and to try out poetry for themselves. This class meets on-line via Zoom two Tuesdays, March 22 and 29, 2022, 6:00-8:00 p.m. In How to Read a Poem (and Maybe Write One) Julie will help budding poets to find their poetic vision and replenish their founts. More information here.

Because You Asked About the Line Between Prose and Poetry

It’s 1972, I’m 15 years old, I’ve been writing seriously for about a year, I’m holed up in the only bathroom of our crappy run-down apartment in East Charlotte, my sister is banging on the locked door, and I’m slumped down in the lukewarm bathwater reading.

LINT

I’m haunted a little this evening by feelings that have no vocabulary and events that should be explained in dimensions of lint rather than words.

I’ve been examining half-scraps of my childhood. They are pieces of distant life that have no form or meaning. They are things that just happened like lint.

And the hair on the back of my neck stands up. Because sometimes it does that when I read stuff.

“Lint.” That’s the whole thing. I turn the page to see if there’s any more, and there isn’t, and my sister yells that I’m a selfish jerk who’s hogged the bathroom long enough and other people live here too.

I read “Lint” again. What the hell is it? I look at the book I’m reading. The cover illustration is a photo of a dark-haired young woman in a lacy blouse, grinning crazily, sitting beside a chocolate cake. The author is Richard Brautigan, a writer I’m only vaguely aware of, and the title is Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970.

I read “Lint” again. What the hell is it? I look at the book I’m reading. The cover illustration is a photo of a dark-haired young woman in a lacy blouse, grinning crazily, sitting beside a chocolate cake. The author is Richard Brautigan, a writer I’m only vaguely aware of, and the title is Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970.

Stories, I think. How is that a story? It’s only four sentences long!

This is three decades before the label “flash fiction” would be invented. “Micro-essay” won’t be a thing until the next century. Maybe this is a prose poem, I think. But the book says Stories.

“Are you in there reading that hippie crap?” my sister yells, and she kicks the door.

I read it a third time. It’s not a prose poem, I decide.

And it’s not a story. Maybe if you’re good enough, audacious enough, don’t care enough about definitions and rules and nomenclature, you can write a story that’s not a story and still call it a story.

Maybe, I think, maybe you just write it and let somebody else figure out what to call it and you keep writing, keep going on to the next thing. Maybe deciding what it is is not your job.

I wrap myself in a ragged blue towel and unlock the door.

“If you used up all the hot water,” she says, “I’m gonna kill you.”

ABOUT LUKE: Luke Whisnant is the author of the poetry chapbooks Street and Above Floodstage, the novel Watching TV with the Red Chinese, and the short story collection Down in the Flood. His chapbook In the Debris Field won the 2018 Bath Flash Fiction International Novella-in-Flash Award, and his flash has been published in many journals including Quick Fiction, Hobart, The Journal of Microliterature, Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine, and CRAFT, where his “What They Didn’t Teach Us” won an Editor’s Choice Award in 2019. Whisnant’s new novel, The Connor Project, will be published by Iris Press in April 2022. He has taught short-form prose workshops for Charlotte Lit, the South Carolina Writers Association, Wildacres Writers Workshop, and in his own classes at East Carolina University.

EXPLORE SHORT FORMS WITH LUKE: Flash is the genre for fast times, with hundreds of journals and websites publishing shorter and shorter work. In this three-week class with Luke, you will learn some common misconceptions about flash; delve briefly into the history of short-form prose, including prose poetry and micro-essays in FLASH 101: FLASH FICTION & MICRO ESSAY. Fiction writers, prose poets, and concise nonfiction writers are all welcome. This class meets via Zoom on three Thursdays, March 17, 24 and 31, 6:00-8:00 p.m. More information here.

Haunted by an Unfinished Book

As a teacher and coach I’ve seen plenty of writers haunted by an abandoned book. They say things like “I didn’t see it through” or “I gave up.” Let’s face it, most of us write with the intention of at least finishing. Though ideally we want the finished manuscript to be published, preferably backed by an agent and a major house. Even if we don’t always vocalize it, we have fantasies that extend way beyond that – bestsellers, literary prizes, movie deals.

As a teacher and coach I’ve seen plenty of writers haunted by an abandoned book. They say things like “I didn’t see it through” or “I gave up.” Let’s face it, most of us write with the intention of at least finishing. Though ideally we want the finished manuscript to be published, preferably backed by an agent and a major house. Even if we don’t always vocalize it, we have fantasies that extend way beyond that – bestsellers, literary prizes, movie deals.

It’s easy to beat yourself up over that unfinished potential best seller, but here’s the truth: every successful writer has at least one abandoned book, probably far more than one. Some books are unfinished, others get lost in the weeds of publishing – never finding an agent or our agent was unable to sell the story.

In some cases we grieve. Other times we reread our lost stories, wince, and thank God they never escaped into the marketplace. Not every book is intended for publication and not every abandoned book is a failure. In fact, I’d say a book is a success if:

- You learned something from writing it.

- You honed your techniques and upped your skill level from the sheer practice of showing up at the computer day after day.

- The process of writing and trying to sell it brought you in contact with people who will be important to your career eventually.

- It propelled you to your next story.

- You developed some scenes or characters who – while perhaps not strong enough to support an entire work of fiction – may find a home in a different story in the future.

I’ll cop to seven dead books – three unfinished and four unsold. They’re under my bed in little rectangular boxes, whose resemblance to coffins is impossible to overlook. But those of you who have taken my classes know, I keep “cut character” and “cut scene” files and raid them on a regular basis. Who knows? Some of my murdered darlings may yet claw their way from the grave and live again in a different form.

ABOUT KIM: Kim Wright is the author of Love in Mid Air, The Unexpected Waltz, The Canterbury Sisters, Last Ride to Graceland, and The Longest Day of the Year. As The Story Doctor, she coaches and offers developmental edits. Kim is a Charlotte Lit Authors Lab faculty member and coach. When she’s not teaching, writing, and editing, she’s often talking about writing on social media.

FIND YOUR NEXT STORY WITH KIM: Successful writers will tell you they often make multiple false starts before settling on a concept that can really go the distance––but exactly where do those original ideas come from? In Generating Story Ideas Kim will teach you how to separate the concepts that are mere glimmers from those that hold narrative gold. More information here.

Understanding the Three Act Structure

What is the three-act structure, really?

Most stories are this: a character takes a journey of change.

Most stories are this: a character takes a journey of change.

Let’s take this one level deeper. At the start, there is something internal the story’s protagonist must learn (such as overcoming an original wound or dispelling a misbelief). The story provides an external problem that forces them to confront their internal need.

Experienced novelists (and screenwriters, playwrights, and memoirists) share a secret: stories recount this journey using the same basic structure. And while there are many ways to skin this cat (including the construct called “Save the Cat”), its essence is the three-act structure.

ACT 1

- Setup: Establish the protagonist, their everyday life (the ordinary world from which they will depart), and their inner desire, wound, or misbelief.

- Inciting Incident: An event forces a change in the character, setting their adventure in motion.

- Plot Point One: The protagonist accepts the challenge and crosses the point of no return.

ACT 2

- Rising Action: The protagonist encounters roadblocks, and allies and enemies, on the way to achieving their goal.

- Midpoint: The protagonist faces their biggest challenge, which threatens to derail their mission.

- Plot Point Two: The protagonist — who has so far been reactive — makes a choice to become proactive.

ACT 3

- Crisis: As the protagonist faces their final challenge, it would seem that all is lost.

- Climax: The protagonist manages to overcome whatever is holding them back. They triumph over the antagonist (or antagonistic forces).

- Denouement: Our hero returns to their previous life, having changed — with their ordinary world having been changed, too. Loose ends are tied up and tension is released.

Think of these nine bullet points as essential scenes or story beats. Consider them to be your guides for a novel, memoir, screenplay, or stage play — a writing journey that is worth the trip, and after which you, too, will be changed.

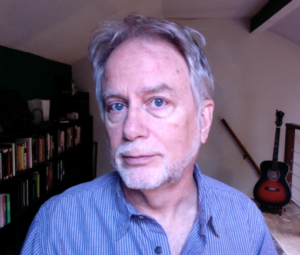

ABOUT PAUL: Charlotte Lit co-founder Paul Reali is a writer and editor, and co-lead of Charlotte Lit’s Authors Lab. He is the author of Creativity Rising, and editor of more than a dozen books and journals on the subject of creativity. His writing has been published in the Winston-Salem Journal, InSpine, Office Solutions, and Lawyers Weekly, among others. His fiction has won the Elizabeth Simpson Smith and Ruth Moose Flash Fiction competitions, and he received a Regional Artist Project Grant from Charlotte’s Arts & Science Council in 2018. Paul has an M.S. in Creativity from SUNY Buffalo State, where he also the managing editor of ICSC Press.

LEARN ABOUT NOVEL WRITING. Join Paul Reali for Novel Structures, Tuesday, March 15, 6-8 p.m., or work intensively with Paul and Meg Rich in the 4-week mostly-asynchronous studio, Novel Jumpstart, beginning April 3. More information here.

New Times, New Voice

Over the last several months, I’ve taken a creative break from my novel project and am working on a new essay collection. In this transition, I’ve encountered an interesting problem. Because I’m what you might call a “method writer,” one who tries to become her characters, I noticed that, even when writing a personal essay, I often slip into the unconscious patterns of my novel’s narrator. I’ve been using her buzzwords, her sentence structures, and her metaphors for so many years, some part of me seems to think they’re mine, too. Most egregious, I’ve even fallen prey to her logical fallacies, the ones I worked so hard to help her overcome by the end!

So, I’ve been actively trying to recultivate my authentic voice. I think sometimes we forget that our voice, in writing and in life, is dynamic; if it doesn’t change over time, it becomes stale and boring to us and likely to our readers. When I first started writing my novel, I was living in the West, teaching angsty teenagers, and interacting with all kinds of people without masks: How could I possibly have the same voice that I have now, working on these essays? In the course of drafting, revising, and polishing that manuscript, I also conceived, bore, and breastfed a human being. So, in order to find my new voice, I needed to spend time unlearning who I was and embracing who I’d become.

The particular essay I’ve been working on intensely over the last few weeks is a doozy. I’m attempting, in 6000 words or less, to fully explore my relationship to reproduction — including several pregnancy losses — and the societal underpinnings of shame attached to some of my experiences. Finding the right register, rhythm, and diction (read: voice) is paramount because I hope this essay will speak to and for those who have experienced this, too. After writing a few paragraphs last week — with a register that felt too submissive and diction that felt too easy — I commented the following, in bold, in the margin: “Remember that you were not comfortable at any point during these experiences. It’s okay for your reader to feel a little uncomfortable, right?” The next few hours were a wonderful experimentation in what that voice might be: a direct, precise woman who isn’t afraid to make her audience a little uncomfortable. Sounds good to me!

To write truly voice-driven work, we must continually define and redefine how we want to communicate; we must adjust to the ways we change over time and to the differing purposes of our work. Often, we have to step outside of the unconscious patterns we’ve built onto every page we’ve already written and say, “Hey! Is that still how you want to sound?” If not, I hope you’ll have the courage to discover what you might write to yourself in the margins.

ABOUT MEG: Megan Rich has written two books, a YA novel and a travel memoir, and is seeking representation for her third, a literary thriller inspired by The Great Gatsby. She took part in the highly-selective Sub-Concentration in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan, for which she completed a thesis of original poetry. In addition, she’s a graduate of the Lighthouse Writers Workshop Book Project program. With fourteen years experience as a creative writing teacher and mentor of students from ages twelve to eighty-five, she is passionate about helping others find and refine their voices on the page.

FIND YOUR VOICE WITH MEG: Learn to create a lasting connection with your readers, by developing your voice in Meg’s upcoming class Creating an Authentic Voice, February 1 and 8 from 6-8 p.m. via Zoom. In this two-session class, we will study voice at a deep level to learn the best techniques and generative exercises for connecting directly and quickly with our readers. In the second session, Meg will provide thoughtful feedback and advice on your work, helping you refine and deepen your voice in revisions. More information here.