Rooftop Inspiration

Wherever our work as writers comes from, I’m just happy that it comes. And I wanted to share my inspiration for my flash fiction, “Ask a Crow.” It started as a poem, based on two things I saw on a rooftop, a crow and a coffee cup. The crow I understood, but a coffee cup? Which lead to a better question, what else doesn’t belong on a roof? From somewhere in my imagination, the bow from a double bass showed up. The bow changed the piece from a poem to a story. Because that bow had to be tossed by someone and tossed no doubt in either joy or anger. Here follows a love story.

Ask a Crow

It used to be her favorite cologne, so I splash some on. I look out the bathroom window, across Division Street. The building across the street has a huge, flat rooftop that takes up too much of my vista. On the rooftop, a wooden water tank. And there, under it, lies the bow for an upright bass. Also, there’s a coffee cup turned cistern, from which a crow bobs and drinks.

The cologne’s extracted from a small, alpine flower—speick. A smell that penetrates. As a punishment during the dark ages, they’d lock people in barns where they were hanging speick flowers to dry. After release, the person could be still be identified as guilty, for weeks—by the smell. Chief crimes for the speick barn were the theft of cattle or sheep, and also adultery.

From the only other room in our apartment, the big room with its one big window, I hear her: Are you going to leave me like this? Are you going to leave me like this? Like the chorus of some old soul tune, one with the verses understood. She’s standing on the window sill, a hand and a foot in each corner.

She turns her head. Her face has folded in on itself, like origami. I grab her by the waist. With my face pressed into her back, I hear her breathing, hard. Wait a minute, she says, Is that my bow?

She jumps down to check the bass case for her bow. I’d felt bad the second I released it. But then, as it sailed over the street, turning end over end, I heard its music. Like the first time I heard her play music: there, at her spring orchestra rehearsal, me the only one in the audience. She sounded so beautiful: I fell in love. Thief and adulterer, she says, all rolled into one.

I jump onto the window sill and go spread-eagled. Like a paratrooper at the jump-door, I turn my hands inside out, my fingers pointing toward Division. I’m set, ready to fly over. Ready to ask the crow: What do I do now? What have I done? How do I get her back? Can I get her back? But he unfolds his wings and flies off, the bow in his beak.

MASTER PERSONAL ESSAYS WITH CHARLES: Be guided—step by step—through the process of writing personal essays. Write a complete essay using prompts, freewriting exercises, feedback, and revision. In this class, you can share your work with others. You may also elect to receive written feedback from the instructor. (New this spring, you’ll have the option to add a detailed critique of your writing for an additional fee. Details will be sent after you register.) This class meets on three Tuesdays, May 11, 18 & 25, 6-7:30 p.m. More info

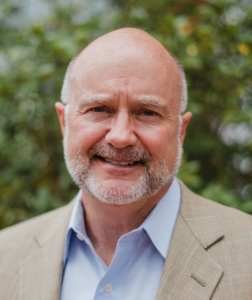

ABOUT CHARLES: Charles Israel, Jr., teaches creative writing at Queens University of Charlotte. His poetry chapbook, Stacking Weather, was published by Amsterdam Press. He’s also had poems and stories in Crazyhorse, Field, The Cortland Review, The Adirondack Review, Nimrod International Journal, Pembroke Magazine, Zone 3, Journal of the American Medical Association, and North Carolina Literary Review. He likes to read ancient epic poetry and contemporary creative nonfiction about voyages and journeys, sports and war. He lives in Charlotte with his wife, Leslie.