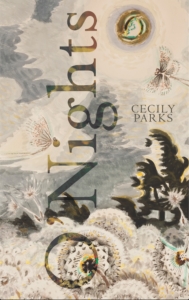

Cecily Parks’ “O’Nights”

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic, hermited study of the natural world, he acknowledges his immersive contemplation might be considered odd. “This was sheer idleness to my fellow townsmen, no doubt; but if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should not have been found wanting.” That standard—of the stars, the moon, the meadow—is the one Cecily Parks’ aspires to in her second collection of poetry, O’Nights (Alice James Books, 2015). Its speaker is the female incarnation of a present-day wanderer trying to commune with what’s left of the wild, one whose solitary forest wanderings mark her even after she finds love and returns to an urban environment.

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic, hermited study of the natural world, he acknowledges his immersive contemplation might be considered odd. “This was sheer idleness to my fellow townsmen, no doubt; but if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should not have been found wanting.” That standard—of the stars, the moon, the meadow—is the one Cecily Parks’ aspires to in her second collection of poetry, O’Nights (Alice James Books, 2015). Its speaker is the female incarnation of a present-day wanderer trying to commune with what’s left of the wild, one whose solitary forest wanderings mark her even after she finds love and returns to an urban environment.

The stars said, Follow us. They drew me deep

into the disheveled spruces to introduce me.

to loss. My fields were ill. They weren’t my fields.

My trees were being killed. They weren’t my trees.

I was nervous that this natural world would see

that I was filthy-footed in silk, a woman

pretending to be a man to trip a pyrotechnic grace. Oh yes,

I wanted the world to be wild again. I believed

I might hold weather in my hands

and mend it . . .

—from “When I Was Thoreau at Night”

O’Nights, which takes its title from an anecdote found in Thoreau’s journal, is split into three sections. In the first, the speaker is alone and spends her days (and nights) closely observing the natural world. While she may be the sole human, her solitude expands to encompass a wider community of the forest where she finds herself in conversation with the wild entities that surround her. She is alone, but not lonely. “Hurricane Song,” the powerful, opening poem, describes the “little kidnapped thrill that comes with drastic weather,” the feeling of being out in a storm’s overture. She’s on the same level as the pines, the grass, and the deer who “flips herself over and over, white tail-spark,/black hoof-sparks, brown wheel.” This leveling serves as a reminder that we humans are animals after all, still part of an ecosystem, still subject to the whims of weather. A sense of restless energy runs through this section as the speaker, eschewing comfort and convention, roams alone.

O’Nights, which takes its title from an anecdote found in Thoreau’s journal, is split into three sections. In the first, the speaker is alone and spends her days (and nights) closely observing the natural world. While she may be the sole human, her solitude expands to encompass a wider community of the forest where she finds herself in conversation with the wild entities that surround her. She is alone, but not lonely. “Hurricane Song,” the powerful, opening poem, describes the “little kidnapped thrill that comes with drastic weather,” the feeling of being out in a storm’s overture. She’s on the same level as the pines, the grass, and the deer who “flips herself over and over, white tail-spark,/black hoof-sparks, brown wheel.” This leveling serves as a reminder that we humans are animals after all, still part of an ecosystem, still subject to the whims of weather. A sense of restless energy runs through this section as the speaker, eschewing comfort and convention, roams alone.

In the book’s second section, the speaker is in the city, deliriously in love, “suspended in the edgy bliss.” Of these 15 poems, two are aubades—poems bidding farewell to a love at dawn. Notwithstanding the speaker’s former forest solitude, loneliness pangs around the edges of these poems. When the lover’s frequent absences are most keenly felt, the speaker’s thoughts go to foxes in their den, and back to the community she found in the natural world where “puddles count the clouds,” and where “the marsh opens its little wet mouths.” These are lush and lovely pieces. The lovers, at last, share time together in “Love Poem” and the longer “Twelve-Wired Bird-of-Paradise:”

We’re afraid we’ll die before we’ve loved each other long enough.

There is no end

to long enough. This is paradise.

The final section of O’Nights is its shortest and least thematically cohesive, but includes the standout lead poem “Bell.” Parks writes beautifully about the wild world in all its seasons and moods. If the birds and flowers tried her by their standard, her keen-eyed poems with would not be found wanting.

September 4X4CLT kicks off Labor Day weekend featuring Cecily Parks, author of O’Nights and Field, Folly, Snow. Parks reads from her work at the release party on Friday August 31 from 6 to 8 pm at SOCO Gallery. Local artists Ruth Ava Lyons and Linda Foard Roberts will also be on hand for the celebration, which is free and open to the public. September 4X4CLT posters with poems and art from these three women will be displayed at over 70 venues in and around Charlotte. On Saturday September 1 from 10 am to 1 pm, Parks will teach a master class in poetry at Charlotte Lit’s studio.